Inspiring restraint - not only in Japanese. Cultural and historical links to bondage

- (not proofread) english version below -

The original version of this text was printed in

Headlines - SM from the scene for the scene #171, Hamburg, July 2019

"[...] it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with;

it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what ties tie ties."

- Donna Haraway[1]

Rope bondage aficionados who want to learn more about techniques, schools and origins of practices beyond improvised ties with a bathrobe belt can hardly avoid being confronted with the history of Japanese restriction arts Shibari or Kinbaku. The string track will lead you to medieval Samurai, who overpowered opponents with rope restraints called Hojojutsu. One learns that bondage practices developed somehow organically out of Japanese everyday culture, since kimonos are also tied, or gifts with a furoshiki. In his highly acclaimed book „The Beauty of Kinbaku“[2], Master „K“ never tires of emphasizing how closely Shibari/Kinbaku is linked to Japanese history, religion, and culture, distinguishing ornamental Japanese bondage from pure restriction measures to which he reduces Western bondage. He refers to Shintoism practiced in Japan, in which Shimenawa (ropes adorned with sacred paper) are used to mark sacred places, and binds the origins of rope aesthetics back to the ancient Japanese Jomon culture, whose pottery is characterized by the decorative use of string.

Early middle Jomon pottery, 5000-4000BC, with cord marks for decoration Tokyo National Museum Photo taken by Chris 73 in January 2005, freely available at //commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Middle_Jomon_Period_rope_pottery_5000-4000BC.jpg under the creative commons cc-by-sa 3.0 license

So when visiting the Museum for Pre- and Early History in Berlin, I flinch. I stand in front of a showcase with decorated vessels, which are presented to me as string ceramics: 2800 B.C., excavated in – Saxony-Anhalt, Germany! There the knot bursts and I intend to appear at the next Bondage-Jam not in an ‚authentic‘ Kimono, but already mentioned bathrobe.

As if bondage were a purely Japanese technique, there is a lack of cultural-historical embedding of bondage practices in Western contexts. At the same time, the repeatedly claimed uniqueness of the genesis of Japanese bondage arts obscures the view of the many other existing red threads that can make us understand that what we do at bondage events is not only something imported and appropriated from another culture, but has long since been complexly interwoven with manifold histories. If we pick up and follow these different threads, they lead us to a variety of surprising origins of the uses and aesthetics of rope practices.

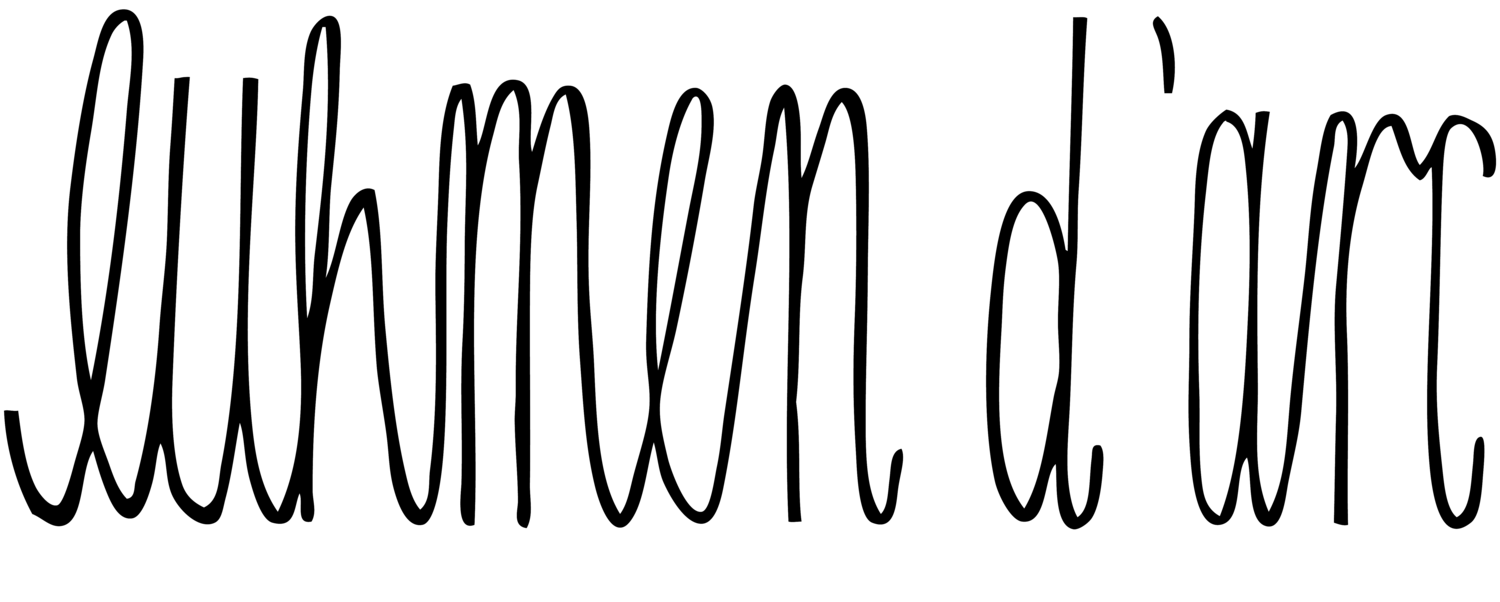

Then we unravel a cable clutter of architectural and decorative cord ceramics from the cultures of Egypt and the Greco-Roman world, the twisted columns of Romanesque architecture, the rope-like twists of wickerwork, the use of arithmetic rope in the European Middle Ages, the depiction of ropes on heraldic banners – for our subject, particularly paradigmatic the so called lacs d’amour ❤ . Not to mention the cross-cultural use of rope as a tool in transport and construction, in seafaring, in sports and as an important component of machines.

Hortus Deliciarum – 12th century Allegory of arithmetic Artist: Herrad von Landsberg (about 1180), CC-PD-Art (PD-old-100)

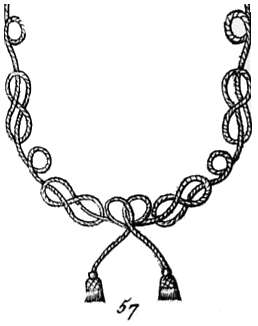

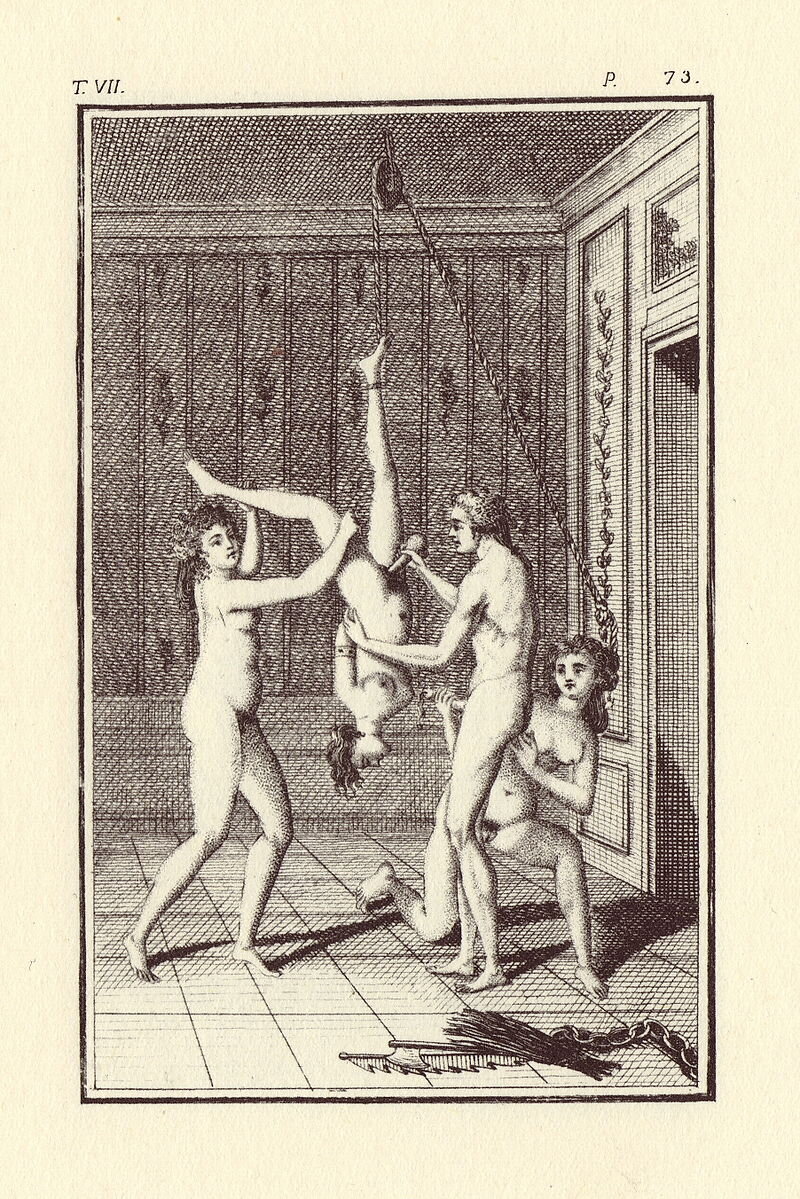

Ropes as a material had an important impact on everyday life all over the world, not only Japan. Also the practice of rope bondage in the West tells its own transformation stories from violent to erotic pleasure practices beyond Japanese martial arts and Kabuki theater. A famous copperplate engraving from Marquis de Sade’s work Justine ou les Malheurs de la vertu from 1787, for example, depicts a person hanging upside down with a sling wrapped around her foot and pulled up over a pulley, who, delivered in suspension, is penetrated with dildos. As cultural historian Iris Därmann points out, this picture is a direct quote that explicitly refers to drawings of torture scenes from the West Indies of the time, published in John Gabriel Stedman’s Narratives of a Five Year’s Expedition against Revolted Negroes of Surinam, which records the sexualized punishments by slave owners. The similarity is astonishing, but „the figure of the stripped black girl was replaced by that of the white girl“ — a movement in which „slave emancipation […] at the same time introduces the emancipation of sadism as an ‚independent‘ sexual practice“[3].

Isaac Cruikshank „The Abolition of the Slave Trade, or the Inhumanity of Dealers in human Flesh exemplified in Captn. Kimber‘s Treatment of a Young Negro Girl of 15 for her Virje [!] Modesty“

Justine ou les Malheurs de la vertu, c. 1800 PD-old-100-expired

How can this change be explained, when once martial scourges find themselves translated into elaborate, consensual, lustful variations? The social anthropologist Edward B. Tylor found the term „survivals“ for this. As survivals he describes fragments of traditional customs and practices from a bygone era that are preserved through the historical development of a culture, but lose their original purpose and undergo a shift in meaning. Significantly, these elements are often found in children’s games, such as playing with a bow and arrow or dressing up as pirates. Rope bondage, which seems archaic in contrast to more modern restriction methods with handcuffs or straitjackets, is also found not only in BDSM fields, but also in (highly controversial!) initiation rites and punishment games in some Scout traditions such as german “Pflöckeln” (attaching the limbs to pillars staked in a square). In role-playing games such as „Robbers and Gendarme“ or playing Cowboys, ropes can be used as lassos and for staged imprisonment, and I leave it to the readers to remember their own childhood bondage games, which can take on countless imaginative forms.[4]

Ties have also gained fame in the performative use between entertainment, stunt and sport, such as so-called escapology, which appeared increasingly around the turn of the century and was popular first as illusionistic tricks in spiritualistic circles and then as show interludes by magicians, with Harry Houdini being considered the most famous figure among escapologists.[5] Especially with regard to the aforementioned slave emancipation, there is an interesting hinge in the figure of the magician Black Herman, who was probably the most prominent African-American escape artist in the 1920s – ’30s. He narratively combined his magic performances with political messages. It is said that he used to let himself be tied to a chair with ropes by audience members and explained that to liberate himself he used those ’secret‘ techniques, which enslaved Africans had already used in order to flee from their slaveholders.[6]

When talking about the art of bondage, the virtuosity and ornamentality of the practices are usually emphasized. However, bondage can also be found in areas that claim to be artistic in the narrower sense. Not only do many bondage scenes include public performances or photographs (the artistic value of which can be disputed in each case), but as a motif that carries meaning, bondage also goes beyond libertine arousal cultures. In Rope Piece by performance artists Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh, for example, bondage becomes a symbol of general entanglements and dependencies. For an entire year, from 1983 to 1984, they remained physically tied to each other only separated by an eight-foot rope, the ends of which they each had laced around their own waist. In an interview, the artists explain that for them the performance is a clear picture of how we are always already tied to other people to survive.:

,,Because we are all individual, we each have our own idea of something we want to do. But we’re together. So we become each other’s cage. We struggle because everybody wants to feel freedom. […] So this piece to me is a symbol of life and human struggle. […] there are cultural issues, men/women issues, ego issues. Sometimes we imagine this piece is like Russia with America. How complicated the play of power.”[7]

Cornelia Parker, The Distance (A Kiss With String Attached), 2003, CC-BY-SA-3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Distance_(A_Kiss_With_Strings_Attached),_2003.jpg

Complexities also manifest themselves in rope bondage and Shibari/Kinbaku. When asked for the reasons of the claustrophilia of bondage enthusiasts, many will say something like this: „Only bound do I feel really free“. A conundrum in which opposites collide. Freedom through restriction, strength through vulnerability, capability through impotence. The world is turned upside down when bonds are generally understood as a metaphor for destructive constraints par excellence (e.g. “It is precisely those artists who are most inclined to think of their art as the manifestation of their personality who are in fact the most in bondage to public taste.“) and emancipatory appeals call for their breaking. We commonly value activity over passivity, freedom over restraint, ability over inability, autonomy over dependency. So why voluntarily submit to limitation and how can one even feel empowered by it? How does lacing lead to wings? Answers are not only to be found in geographically shaped historicizations.

„He still felt the evening wind between him and the wolf as the animal sprang at him. The man made sure he obeyed his ties. With the care he had long been practicing, he gripped the wolf by the neck. Affection for a being his equal rose in him, for the upstanding in the lowly. In a movement like the swoop of a huge bird – and now he knew for sure that flying was only made possible by very particular bonds – he threw himself at it and brought it to the ground. As if intoxicated, he sensed he had now lost the deadly supremacy of free limbs which let humans be beaten. His freedom in this fight was in harmonizing each twist of his limbs to the ties – the freedom of the panther, the wolves and the wild flowers swaying in the evening breeze.“

– Ilse Aichinger: „The Bound Man“

Looking at the thing itself, the promises of restrictions seem to be based on the insight that existential experiences of pathos – i.e. incidents, exposure, incapacity, vulnerability, sensitivity, devotion, submission and nonsovereignty – are inseparable from life and that every activity is deeply embedded into passivity. Bondage is part of the infamous ‚madness‘ of ascetic self-limitation like reclusion or fasting, by means of which the body consciously and directly exposes itself to forces that otherwise subliminally drive it about. These forces can be social structures like power hierarchies or they can be more existential aspects of the human condition between natality and mortality, pain and joy, being formed by what is not originally yours and dependent of others. Acts of self-limitation and exhaustion, such as bondage, can give form to these elusive forces in order to make them consciously experienceable and thus reflectable – without, of course, ever being able to master them. By no longer being able to do something (for example, to move), we not only make something impossible, but also open up a new space of possibilities that can only be experienced in non-doing and non-capability.

We don’t even need to go looking into deviant niches such as BDSM and Kink[8], we can just take itself at its word. We talk about being tied up in knots, are fit to be tied or cutting the ties with someone. To get accustomed to a task we do networking and someone shows us the ropes – but it is said that if you give one enough rope he will hang himself – since deliberately giving somebody enough freedom seems to lead them to make a mistake and get into trouble. What might help then is to follow a golden thread, promise that there are no strings attached or that one’s word is one’s bond, while in the financial system bonds refer to the ambivalent obligations resulting from loans, which express belonging, but also dependence.

Paradoxically, we allow ourselves to be ‚tied up‘ in order to expand our scope of action. Entanglements and enmeshments, for example, point on the one hand to a kind of captivity and thus passivation, on the other hand the involvement in certain circumstances can in turn provide new insights and possibilities. Media-theoretical discourses on the effects of the internet or world wide web – which take up the archaic-looking rope practices – describe how we hang passively on technological devices, but can also enter into new modes of relations and agency through them. The communicative aspect is reflected in bondage: the rope, wrapped around one’s own body, touching one, maintains contact with the person tieing one up, and figuratively stands for dialogue and connection, like the tightly taut threads of the cup phones from childhood. In order to be able to make contact at all, however, one needs the condition for the identity-creating and thus emancipating and activating experience of childbirth, which as the first rope experience among mammals is already embodied in the umbilical cord as a form of rope, the condition of which in turn is a kind of existential bondage – the mother-child relationship is not for nothing described by sentimental prenatal consultants with the developmental psychological concept of bonding.

© Foto H.-P.Haack. Note here how rope bondage is also used as a tool to support the birthing process.

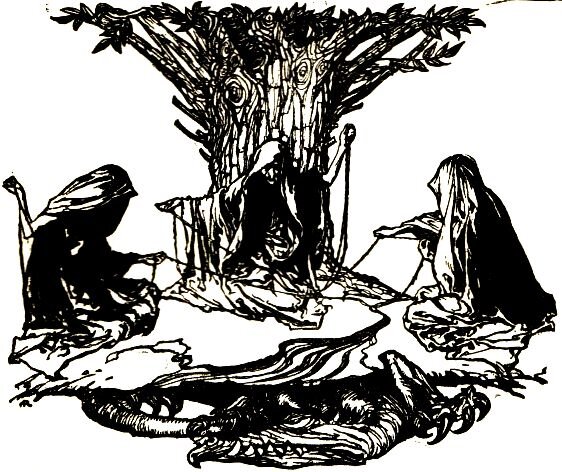

Fateful entanglements can also be understood as a form of bondage, of something passively occurring. In mythological narratives this can be found in Plato’s famous cave parable, in which people are imagined bound in a way that they cannot turn their heads and always look straight ahead, holding shadow plays for real life; or in the rope of fate woven by the Norns of Norsmythology.[9] From a mythological point of view, we hang like puppets on these ropes that we have no control over. The belief in our autonomous power to act proves to be an illusionary misbelief. And yet we do not only hang passively, since we actively participate in shaping our experience, in an entanglement of determining and being determent.

Norns weaving destiny, by Arthur Rackham (1912), PD_US

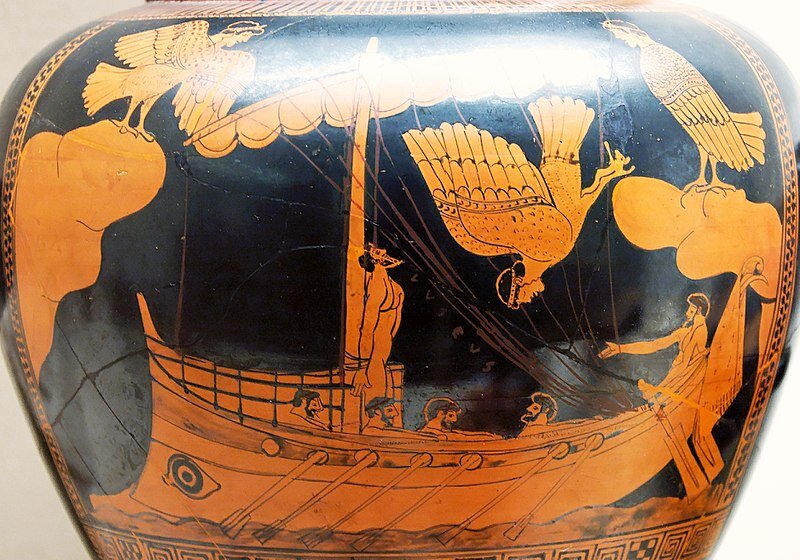

The complicated nexus of liberation through bondage is beautifully illustrated in the figure of Odysseus, who prominently uses bondage as a means of opening up a possibility space by restricting himself, when he is bound to his ship’s mast with ropes in order to be able to listen to the seductive song of the sirens without being seduced by them and thus die.

Pragmatically, the hero of the Odyssey could also have stuffed wax into his ears and continued sailing. What he does here with the rope is similar to the kinky bondage practices, a technique that generates pleasure, also by playing with danger, risks and power relations.

Odysseus and the Sirens. Detail from an Attic red-figured stamnos, ca. 480-470 BC. From Vulci.

How ropes are woven into a history of power is evident in the domestication of animals by reins and leashes or in direct contexts of violence such as hanging by a noose or in areas such as torture and slavery.[10] It is striking that practices of criticism of power constellations that cause suffering do not, however, strip off motifs from the rope chains as insignia of power, but in turn appropriate them for their own purposes and reoccupy them imaginatively. For example, practices of passive resistance are known in which one is tied to trees, buildings, rails or other people. These protests responds to political domination with an exaggerated embodiment of one’s own lack of domination and use the power of becoming vulnerable. In addition, the ties create bonds of togetherness that make it difficult for opponents to reach the objects to which they are tied.[11] Strategically, the ruling schemata is not simply being withdrawn – the answer to constricting powers here is not a demonstration of unstrangling and freedom. On the contrary, the enemy is beaten with its own weapons. Instead of undoing the shackles, the resistance lies in trying to deal with the constraints differently while staying within the shackles. It’s a mode of reclaiming. Michel Foucault has described this in his famous definition of critique as not asking “how not to be governed at all,” but “how not to be governed like that, by that, in the name of those principles, with such and such an objective in mind and by means of such procedures.”[12]. Starting from the premise of powerful social and cultural structures to which man is ‚tied‘ and from which he can never completely liberate himself from and enter a somehow powerless outside, he describes how, in the playing field of power, the subjects have room for manoeuvre: to play along and negotiate the rules of the game. The decisive question is therefore not how to break the shackles, but looking for innovative ways of agency within bondage and looking for the best possible ways of bonding: who and what do we really want to submiss to? In this way, rope bondage could be understood as a way of accepting and playing with being governed, but only if one considers its nature and reasons to be satisfactory. In this way, one can enter into the movement of de-subjugation through submission.

Ostra Studio, circa 1935CC-PD-MarkPD-old-70

Bondage arts and practices could then become conceivable as possibilities for cultivating, one could say: vita passiva, with which the promises and necessities of an attitude interested in passivity, pathos and passion can be experienced bodily. Bondage does not only affect the body from the outside. The still and fixed positions bring hidden things to light, for example that corporeality is inexorably open, vulnerable, mortal, shameful and porous in its boundaries. In his phenomenological confrontations with sexual desire, Jean-Paul Sartre describes such processes as one’s wish to make the other person only flesh and thus revealing ourselves as just flesh. Sartre writes that the Other’s facticity is usually hidden and masked by clothes, make-up, beards and gestures, but that there will always come a time when the mask falls and the Other is exposed in the pure contingency of his presence, that is, in his flesh. A body is that object which is always more-than-a-body, because it is never given to me without its surroundings, it always points beyond itself in space and in time. The flesh of the body is what the body is reduced to, when there is no surrounding, no context, no relationships. Flesh is hidden above all by gestures and movements, that position human beings as beings in a position in a surrounding, a being who acts in situations in relation to the world and thus appears as body-in-situation. This is described by Sartre with the term grace: “Nothing is less ‘in the flesh’ than a dancer even though she is nude. Desire is an attempt to strip the body of its movements as of its clothing and to make it exist as pure flesh; it is an attempt to incarnate the Other’s body“.[13] Gracefulness for Sartre is the „moving image of necessity and freedom“, it is grounded in the active body. Practices such as bondage, which prevent the execution of movements, lead to the absence of these components and reveal the flesh of the person. The desire for making a body adopt obscene positions which expose it to all disguises and which reveal the inertia of its flesh is described by Sartre as sadistic. The sadist deprives the body of its situation, capturing and containing its freedom by looking for the fleshiness that lies hidden underneath all doing and making. The sadist wants his*her victim’s body as being “entirely flesh, panting and obscene, it keeps the position that the torturers have given to it, not that which it would have taken by itself, the cords which bind it sustain it as an inert thing and, by that, it has ceased to be the object which moves spontaneously“[14]. The French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas, in turn, strikingly describes the possible shame resulting from this by means of the figure of bondage: „What appears in shame is thus precisely being tied to oneself, the radical impossibility of escaping ourselves, of hiding from ourselves: the unforgivable self-presence of the ego. We are ashamed of our nakedness when it openly reveals our being, our intimacy“. And what if the confrontation with this state is now deliberately (masochistically) provoked? A fascination for such movements in BDSM practices is again expressed by the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, since for him the „paradoxical character of shame is consciously made an object in them, in order to transform it into lust. […] For here a passive subject – the masochist – is so enthusiastic about his own, infinitely overwhelming passivity that he renounces his capacity as a subject […]. Hence the ceremonial armor of the snares and shackles, […] of all kinds of bondage, with the help of which the masochistic subject tries in vain to hold back and ironically fix that transferable passivity that it deliciously surpasses everywhere“.[15]

If such observations are elevated to a concept such as the art of not being governed in a specific a way (but nonetheless being governed and bound), this would be accompanied by an appreciation not only of what people create and accomplish, but also of what they endure and suffer. The freedom so often longed for would then not turn out to be a kind of stock that could be disposed of. Freedom emerges momentarily in the constantly new, wayward, even energy-sapping handling of afflictions, resistance, indeterminacy and in the recognition of complex entanglements.

Cat's cradle: position 1, the cradle Originally from Squareman, Clarence (1916).

My Book of Indoor Games, Gutenberg.org. PD-US

For the feminist science theorist Donna Haraway such an abandonment of traditional narratives of autonomy and instead recognition of fundamental interdependencies is an unavoidable premise for living well together on this planet in the long term. To illustrate her thinking, she uses an image that is also taken from the world of strings and their potential for force-generating entanglements: String-Figures, which some readers might also know from their childhood as pattern-forming thread games. In these games, which have been and are played in a variety of cultures around the globe, the aim is to tie a closed cord around fingers and hands so that braided figures gradually form in the space in between. Their emergence can be accompanied by a narration that illustrates the pattern.

The back and forth winding of the string patterns in its playfulness points to larger things, such as „the fact that actors do not precede action, that relations take precedence“. Thread games also follow an intertwining of activity and passivity, which requires a thinking of the ‚in-between‘: „two pairs of hands are needed, and in each successive step, one is ‚passive‘, offering the result of its previous operation, a string entanglement, for the other to operate, only to become active again at the next step, when the other presents the new entanglement. But it can also be said that each time the ‚passive‘ pair is the one that holds, and is held by the entanglement, only to ‚let it go‘ when the other one takes the relay.“[16] Out of the entanglement of activity and passivity, Haraway develops a model in which relationships and interconnections are central: polymorphic networks that enable unexpected sides of one’s own sensuous embodiment. Above all, however, the fundamental mutual interconnectedness is accompanied by a concept of responsibility that the string and bondage games illustrate:

„In passion and action, detachment and attachment, this is what I call cultivating response-ability [sic!]; that is also collective knowing and doing, an ecology of practices. Whether we asked for it or not, the pattern is in our hands.“[17]

'Mme Hitchen with string bear' ~ (Anishinaabe) ~ Long Lake, Ontario 1916, F.W. Waugh, CMoH, CC-PD-old-70-expired

Which bondage patterns and stories are in our hands is in risk of being overlooked if we only exoticize the origins of rope bondage. This includes, as Haraway’s cord games show, also the stories that have yet to be realized as possible future stories. Rope bondage, as romanticizing as it may sound, thus brings with it an utopian moment in which it becomes tangible that the task of grasping one’s own possibilities and breaking out of a preordained destiny does not only consist in „loosening or breaking the many bonds during our lives“,[18] but also to create bonds, to get tied up, to get entangled and to search together for new states of being within the existing bonds. As an adaptation of Foucault’s formulation, bondage arts point out to deal with limitations, restrictions, ties and untying in an attentive and different way. The inherent vulnerability and ultimately mortality revealed by bondage not only makes the practice a breeding ground for intoxicating sensations that promise a delightful ‚kick‘, but also has the potential to generate ethical appeals for the perception of mutual connectedness, care and responsibility for one another. At least this is, what I have experienced and like to share.

[1] Donna J. Haraway: SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far, in: Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, Issue 3, November 2013, at: https://adanewmedia.org/2013/11/issue3-haraway/ (last accessed on 20.03.2019).

[2] Master "K": The Beauty of Kinbaku (or everything you ever wanted to know about Japanese erotic bondage when you suddenly realized you didn't speak Japanese), USA: King Cat Ink., 2008.

[3] Iris Därmann: Shame and Whip Violence, Pornographic Investiture Scenes in the Anti-Slavery Movement and in Marquis de Sade. In: Daniel Tyradellis (ed. for the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden): Shame. 10 Essays. Accompanying book to the exhibition: 100 reasons to be ashamed, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2017, p. 99.

[4] Edward B. Tylor: Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom, London: John Murray, 1871.

[5 ] In this admission rite, which is also described as a ritual form of punishment, the child is tied stretched out by the hands and feet to four pegs stuck into the ground in a square. Pegging is now strongly criticized by scout associations and is seen as a possible form of child abuse. Cf.: Markuc C. Schulte von Drach: Kein harmloses Spiel, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 5.12.2014, at: http://www.sueddeutsche.de/panorama/pfadfinder-ritual-pflocken-kein-harmloses-spiel-1.2250396 (last accessed on 10.06.18).

[6 ] See: Edwin A Dawes: The Great Illusionists, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, 1979. And: T.I.E.S. - The International Escapologist Society, at: http://www.tiesociety.webs.com (last accessed on 24.06.2018).

[7 ] Cf.: George Patton: Black Jack: A Drama of Magic, Mystery and Legerdemain, Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2009.

[8] Cf: Frank Cullen and Florence Hackerman: Vaudeville, Old and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, London: Routledge, 2006, p. 114.

[9 ] Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh: One Year Art/Life Performance: Interview with Alex and Allyson Grey (1984), in: Kristine Stiles (ed.): Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings, University of California Press, 1996, pp. 907ff.

[10 ] Sadie Plant draws attention to the genesis of archaic media of textile processing associated with cords and ropes into modern technologies:"Media become interactive and hyperactive, the multiplicitous components of an immersive zone which 'does not begin with writing; it is directly related rather to the weaving of elaborate figured silks. The yarn is neither metaphorical nor literal, but quite simply material, a gathering of threads which twist and turn through the story of computing, technology, the sciences and arts. In and out of the punched holes of automated looms, up and down through the ages of spinning and weaving, back and forth through the fabrication of fabrics, shuttles and looms, cotton and silk, canvas and paper, brushes and pens, typewriters, carriages, telephone wires, synthetic fibers, electrical filaments, silicon strands, fiber-optic cables, pixeled screens, telecom lines, the World Wide Web, the Net, and matrices to come." Sadie Plant: Zeros + Ones. Digital women and the new technoculture, London: Fourth Estate, 1998, p. 12.

[11 ] In addition, the mythological significance of the many small ropes, woven threads and cords can be pointed out, on the occasion of which the media scholar Gunnar Schmidt refers to the "coupling of woman and thread" in Arachne and many others: "Klotho, Neith, Penelope, Philomela, Holda, Zirze, Kalypso, Helena, Pandora, Paivatar, Chih-Nii, Habetrot - when it comes to spinning and weaving, mythical storytelling presents itself across cultures as a cosmos of the feminine." Gunnar Schmidt: Aesthetics of the thread. Zur Medialisierung eines Materials in der Avantgardekunst, Bielefeld: transcript, 2007, p 13. Of course, the practices of bondage and shibari/kinbaku also have their gender-specific characteristics, for example the larger number of male riggers and female 'bunnies' - a fact that can only be alluded to in this context.

[12] "She alone allows me to hear the song; but you bind me tightly so that I cannot move a limb, / Standing upright on the mast, with ropes tightly wrapped around me. / But I beseech you, and command the ropes to be loosed; / Hasten then to bind me still tighter with several bands." Homer: Odyssey, (original title: ἡ Ὀδύσσεια - hē Odýsseia) translated by Johann Heinrich Voß, Frankfurt aM: Insel, 1990, p. 200.

[13 ] Cf. e.g. Neville Twitchell: The Politics of the Rope, Bury St. Edmunds: Arena Books, 2012.

[14] Cf. inter alia Black Lives Matter activists go on trial over protest in Nottingham, Man and three women accused of unlawful obstruction of highway as court hears they lay across streetcar lines while tied together, in: The Guardian, UK News, 03.11.2016, at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/nov/03/black-lives-matter-uk-activists-trial-protest-nottingham (last accessed on 26.06.2018); or: Protesters Tie Themselves to Trees in Bid to Save Them, in: L.A. Times, The Local Review, 23.02.1999, at: http://articles.latimes.com/1999/feb/23/local/me-10815 (last accessed on 26.06.2018).

[15 ] Michel Foucault: Was ist Kritik?, (original title: Qu'est-ce que la critique?) transl. by Walter Seitter, Berlin: Merve, 1992, p. 11.

[16] Ibid, p. 12.

[17 ] Jean-Paul Sartre, quoted without exact reference in Giorgio Agamben: Nacktheiten, transl. by Andreas Hiepko, Berlin: Fischer, 2010, p. 125.

[18] Jean-Paul Sartre: Das Sein und das Nichts. Versuch einer phänomenologischen Ontologie [org. L'Être et le Néant,1943], transl. by Justus Streller et.al., Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1990, p. 699.

[19] Sadism would be understood here as "instrumentalization that dissolves the intended reciprocal incarnation and turns the other into a thing-under-things", in: Knut Berner: Medusas Epigenese. Jean-Paul Sartre and the Development of the Evil Eye, in: Behausungen des Bösen: Epigenesis; Thanatology; Aesthetics; Anthropology, Münster: Lit Verlag, 2013, p. 31.

[20] Sartre: Das Sein und das Nichts, Versuch einer phänomenologischen Ontologie (Orig. L'Être et le Néant,1943), transl. by Justus Streller et.al., Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1990, p. 511.

[21] Ibid, p. 513.

[22] Quoted by Giorgio Agamben in: Was von Auschwitz bleibt - Das Archiv und der Zeuge, transl. by Stefan Monhardt, Frankfurt aM: Suhrkamp, 2003, p. 93ff.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Donna Haraway: Intertwined Notes: Gifts and Debts, in Documenta 13: 100 Notes - 100 Thoughts, vol. 33, Berlin/Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 2012, p. 17.

[25] Donna Haraway: Staying with the Trouble, Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures (Experimental Futures: Technologocal Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices), Durham & London, Duke University Press, 2016, p. 14.

[26] Ibid, p. 34.

[27] Nathalie Sarthou-Lajus: Lob der Schulden, transl. by Claudia Hamm, Berlin: Klaus Wagenbach 2013, p. 86.

- ENGLISH -

"[...] it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with;

it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what ties tie ties."

- Donna Haraway[1]

Rope bondage aficionados who want to learn more about techniques, schools and origins of practices beyond improvised ties with a bathrobe belt can hardly avoid being confronted with the history of Japanese restriction arts Shibari or Kinbaku. The string track will lead you to medieval Samurai, who overpowered opponents with rope restraints called Hojojutsu. One learns that bondage practices developed somehow organically out of Japanese everyday culture, since kimonos are also tied, or gifts with a furoshiki. In his highly acclaimed book "The Beauty of Kinbaku"[2], Master "K" never tires of emphasizing how closely Shibari/Kinbaku is linked to Japanese history, religion, and culture, distinguishing ornamental Japanese bondage from pure restriction measures to which he reduces Western bondage. He refers to Shintoism practiced in Japan, in which Shimenawa (ropes adorned with sacred paper) are used to mark sacred places, and binds the origins of rope aesthetics back to the ancient Japanese Jomon culture, whose pottery is characterized by the decorative use of string.

Early middle Jomon pottery, 5000-4000BC, with cord marks for decoration Tokyo National Museum Photo taken by Chris 73 in January 2005, freely available at //commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Middle_Jomon_Period_rope_pottery_5000-4000BC.jpg under the creative commons cc-by-sa 3.0 license

So when visiting the Museum for Pre- and Early History in Berlin, I flinch. I stand in front of a showcase with decorated vessels, which are presented to me as string ceramics: 2800 B.C., excavated in - Saxony-Anhalt, Germany! There the knot bursts and I intend to appear at the next Bondage-Jam not in an 'authentic' Kimono, but already mentioned bathrobe.

As if bondage were a purely Japanese technique, there is a lack of cultural-historical embedding of bondage practices in Western contexts. At the same time, the repeatedly claimed uniqueness of the genesis of Japanese bondage arts obscures the view of the many other existing red threads that can make us understand that what we do at bondage events is not only something imported and appropriated from another culture, but has long since been complexly interwoven with manifold histories. If we pick up and follow these different threads, they lead us to a variety of surprising origins of the uses and aesthetics of rope practices. Then we unravel a cable clutter of architectural and decorative cord ceramics from the cultures of Egypt and the Greco-Roman world, the twisted columns of Romanesque architecture, the rope-like twists of wickerwork, the use of arithmetic rope in the European Middle Ages, the depiction of ropes on heraldic banners - for our subject, particularly paradigmatic the so called lacs d'amour ❤ . Not to mention the cross-cultural use of rope as a tool in transport and construction, in seafaring, in sports and as an important component of machines.

Hortus Deliciarum - 12th century Allegory of arithmetic Artist: Herrad von Landsberg (about 1180), CC-PD-Art (PD-old-100)

Ropes as a material had an important impact on everyday life all over the world, not only Japan. Also the practice of rope bondage in the West tells its own transformation stories from violent to erotic pleasure practices beyond Japanese martial arts and Kabuki theater. A famous copperplate engraving from Marquis de Sade's work Justine ou les Malheurs de la vertu from 1787, for example, depicts a person hanging upside down with a sling wrapped around her foot and pulled up over a pulley, who, delivered in suspension, is penetrated with dildos. As cultural historian Iris Därmann points out, this picture is a direct quote that explicitly refers to drawings of torture scenes from the West Indies of the time, published in John Gabriel Stedman's Narratives of a Five Year's Expedition against Revolted Negroes of Surinam, which records the sexualized punishments by slave owners. The similarity is astonishing, but "the figure of the stripped black girl was replaced by that of the white girl" - a movement in which "slave emancipation [...] at the same time introduces the emancipation of sadism as an 'independent' sexual practice"[3].

Isaac Cruikshank „The Abolition of the Slave Trade, or the Inhumanity of Dealers in human Flesh exemplified in Captn. Kimber‘s Treatment of a Young Negro Girl of 15 for her Virje [!] Modesty“

Justine ou les Malheurs de la vertu, c. 1800 PD-old-100-expired

How can this change be explained, when once martial scourges find themselves translated into elaborate, consensual, lustful variations? The social anthropologist Edward B. Tylor found the term "survivals" for this. As survivals he describes fragments of traditional customs and practices from a bygone era that are preserved through the historical development of a culture, but lose their original purpose and undergo a shift in meaning. Significantly, these elements are often found in children's games, such as playing with a bow and arrow or dressing up as pirates. Rope bondage, which seems archaic in contrast to more modern restriction methods with handcuffs or straitjackets, is also found not only in BDSM fields, but also in (highly controversial!) initiation rites and punishment games in some Scout traditions such as German "Pflöckeln" (attaching the limbs to pillars staked in a square). In role-playing games such as "Robbers and Gendarme" or playing Cowboys, ropes can be used as lassos and for staged imprisonment, and I leave it to the readers to remember their own childhood bondage games, which can take on countless imaginative forms.[4].

Ties have also gained fame in the performative use between entertainment, stunt and sport, such as so-called escapology, which appeared increasingly around the turn of the century and was popular first as illusionistic tricks in spiritualistic circles and then as show interludes by magicians, with Harry Houdini being considered the most famous figure among escapologists.[5] Especially with regard to the aforementioned slave emancipation, there is an interesting hinge in the figure of the magician Black Herman, who was probably the most prominent African-American escape artist in the 1920s - '30s. He narratively combined his magic performances with political messages. It is said that he used to let himself be tied to a chair with ropes by audience members and explained that to liberate himself he used those 'secret' techniques, which enslaved Africans had already used in order to flee from their slaveholders.[6].

When talking about the art of bondage, the virtuosity and ornamentality of the practices are usually emphasized. However, bondage can also be found in areas that claim to be artistic in the narrower sense. Not only do many bondage scenes include public performances or photographs (the artistic value of which can be disputed in each case), but as a motif that carries meaning, bondage also goes beyond libertine arousal cultures. In Rope Piece by performance artists Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh, for example, bondage becomes a symbol of general entanglements and dependencies. For an entire year, from 1983 to 1984, they remained physically tied to each other only separated by an eight-foot rope, the ends of which they each had laced around their own waist. In an interview, the artists explain that for them the performance is a clear picture of how we are always already tied to other people to survive:

"Because we are all individuals, we each have our own idea of something we want to do. But we're together. So we become each other's cage. We struggle because everybody wants to feel freedom. [...] So this piece to me is a symbol of life and human struggle. [...] there are cultural issues, men/women issues, ego issues. Sometimes we imagine this piece is like Russia with America. How complicated the play of power."[7]

Cornelia Parker, The Distance (A Kiss With String Attached), 2003, CC-BY-SA-3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Distance_(A_Kiss_With_Strings_Attached),_2003.jpg

Complexities also manifest themselves in rope bondage and Shibari/Kinbaku. When asked for the reasons of the claustrophilia of bondage enthusiasts, many will say something like this: "Only bound do I feel really free". A conundrum in which opposites collide. Freedom through restriction, strength through vulnerability, capability through impotence. The world is turned upside down when bonds are generally understood as a metaphor for destructive constraints par excellence (e.g. "It is precisely those artists who are most inclined to think of their art as the manifestation of their personality who are in fact the most in bondage to public taste.") and emancipatory appeals call for their breaking. We commonly value activity over passivity, freedom over restraint, ability over inability, autonomy over dependency. So why voluntarily submit to limitation and how can one even feel empowered by it? How does lacing lead to wings? Answers are not only to be found in geographically shaped historicizations.

"He still felt the evening wind between him and the wolf as the animal jumped at him. The man made sure he obeyed his ties. With the care he had long been practicing, he gripped the wolf by the neck. Affection for a being his equal rose in him, for the upstanding in the lowly. In a movement like the swoop of a huge bird - and now he knew for sure that flying was only made possible by very particular bonds - he threw himself at it and brought it to the ground. As if intoxicated, he sensed he had now lost the deadly supremacy of free limbs which let humans be beaten. His freedom in this fight was in harmonizing each twist of his limbs to the ties - the freedom of the panther, the wolves and the wild flowers swaying in the evening breeze."

- Ilse Aichinger: "The Bound Man"

Looking at the thing itself, the promises of restrictions seem to be based on the insight that existential experiences of pathos - i.e. incidents, exposure, incapacity, vulnerability, sensitivity, devotion, submission and nonsovereignty - are inseparable from life and that every activity is deeply embedded into passivity. Bondage is part of the infamous 'madness' of ascetic self-limitation like reclusion or fasting, by means of which the body consciously and directly exposes itself to forces that otherwise subliminally drive it about. These forces can be social structures like power hierarchies or they can be more existential aspects of the human condition between natality and mortality, pain and joy, being formed by what is not originally yours and dependent of others. Acts of self-limitation and exhaustion, such as bondage, can give form to these elusive forces in order to make them consciously experienceable and thus reflectable - without, of course, ever being able to master them. By no longer being able to do something (for example, to move), we not only make something impossible, but also open up a new space of possibilities that can only be experienced in non-doing and non-capability.

We don't even need to go looking into deviant niches such as BDSM and Kink[8], we can just take itself at its word. We talk about being tied up in knots, are fit to be tied or cutting the ties with someone. To get accustomed to a task we do networking and someone shows us the ropes - but it is said that if you give one enough rope he will hang himself - since deliberately giving somebody enough freedom seems to lead them to make a mistake and get into trouble. What might help then is to follow a golden thread, promise that there are no strings attached or that one's word is one's bond, while in the financial system bonds refer to the ambivalent obligations resulting from loans, which express belonging, but also dependence.

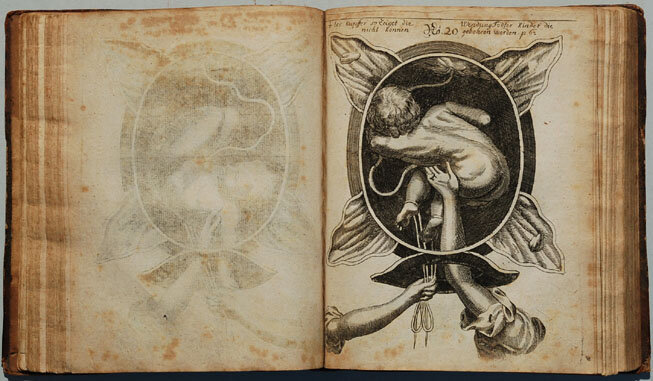

Paradoxically, we allow ourselves to be 'tied up' in order to expand our scope of action. Entanglements and enmeshments, for example, point on the one hand to a kind of captivity and thus passivation, on the other hand the involvement in certain circumstances can in turn provide new insights and possibilities. Media-theoretical discourses on the effects of the internet or world wide web - which take up the archaic-looking rope practices - describe how we hang passively on technological devices, but can also enter into new modes of relations and agency through them. The communicative aspect is reflected in bondage: the rope, wrapped around one's own body, touching one, maintains contact with the person tying one up, and figuratively stands for dialogue and connection, like the tightly taut threads of the cup phones from childhood. In order to be able to make contact at all, however, one needs the condition for the identity-creating and thus emancipating and activating experience of childbirth, which as the first rope experience among mammals is already embodied in the umbilical cord as a form of rope, the condition of which in turn is a kind of existential bondage - the mother-child relationship is not for nothing described by sentimental prenatal consultants with the developmental psychological concept of bonding.

Photo H.-P.Haack. Note here how rope bondage is also used as a tool to support the birthing process.

Fateful entanglements can also be understood as a form of bondage, of something passively occurring. In mythological narratives this can be found in Plato's famous cave parable, in which people are imagined bound in a way that they cannot turn their heads and always look straight ahead, holding shadow plays for real life; or in the rope of fate woven by the Norns of Norsmythology.[9] From a mythological point of view, we hang like puppets on these ropes that we have no control over. The belief in our autonomous power to act proves to be an illusionary misbelief. And yet we do not only hang passively, since we actively participate in shaping our experience, in an entanglement of determining and being determent.

Norns weaving destiny, by Arthur Rackham (1912), PD_US

The complicated nexus of liberation through bondage is beautifully illustrated in the figure of Odysseus, who prominently uses bondage as a means of opening up a possibility space by restricting himself, when he is bound to his ship's mast with ropes in order to be able to listen to the seductive song of the sirens without being seduced by them and thus die. Pragmatically, the hero of the Odyssey could also have stuffed wax into his ears and continued sailing. What he does here with the rope is similar to the kinky bondage practices, a technique that generates pleasure, also by playing with danger, risks and power relations.

Odysseus and the Sirens. Detail from an Attic red-figured stamnos, ca. 480-470 BC. From Vulci.

How ropes are woven into a history of power is evident in the domestication of animals by reins and leashes or in direct contexts of violence such as hanging by a noose or in areas such as torture and slavery.[10] It is striking that practices of criticism of power constellations that cause suffering do not, however, strip off motifs from the rope chains as insignia of power, but in turn appropriate them for their own purposes and reoccupy them imaginatively. For example, practices of passive resistance are known in which one is tied to trees, buildings, rails or other people. These protests responds to political domination with an exaggerated embodiment of one's own lack of domination and use the power of becoming vulnerable. In addition, the ties create bonds of togetherness that make it difficult for opponents to reach the objects to which they are tied.[11] Strategically, the ruling schemata is not simply being withdrawn - the answer to constricting powers here is not a demonstration of unstrangling and freedom. On the contrary, the enemy is beaten with its own weapons. Instead of undoing the shackles, the resistance lies in trying to deal with the constraints differently while staying within the shackles. It's a mode of reclaiming. Michel Foucault has described this in his famous definition of critique as not asking "how not to be governed at all," but "how not to be governed like that, by that, in the name of those principles, with such and such an objective in mind and by means of such procedures."[12]. Starting from the premise of powerful social and cultural structures to which man is 'tied' and from which he can never completely liberate himself from and enter a somehow powerless outside, he describes how, in the playing field of power, the subjects have room for manoeuvre: to play along and negotiate the rules of the game. The decisive question is therefore not how to break the shackles, but looking for innovative ways of agency within bondage and looking for the best possible ways of bonding: who and what do we really want to submiss to? In this way, rope bondage could be understood as a way of accepting and playing with being governed, but only if one considers its nature and reasons to be satisfactory. In this way, one can enter into the movement of de-subjugation through submission.

CC-PD-MarkPD-old-70, Ostra Studio, circa 1935, Source http://www.leslarmesderos.com/site/sscat2_en.php?page=0&ordre=id&sens=desc&id=15&themebase=2

Bondage arts and practices could then become conceivable as possibilities for cultivating, one could say: vita passiva, with which the promises and necessities of an attitude interested in passivity, pathos and passion can be experienced bodily. Bondage does not only affect the body from the outside. The still and fixed positions bring hidden things to light, for example that corporeality is inexorably open, vulnerable, mortal, shameful and porous in its boundaries. In his phenomenological confrontations with sexual desire, Jean-Paul Sartre describes such processes as one's wish to make the other person only flesh and thus revealing ourselves as just flesh. Sartre writes that the Other's facticity is usually hidden and masked by clothes, make-up, beards and gestures, but that there will always come a time when the mask falls and the Other is exposed in the pure contingency of his presence, that is, in his flesh. A body is that object which is always more-than-a-body, because it is never given to me without its surroundings, it always points beyond itself in space and in time. The flesh of the body is what the body is reduced to, when there is no surrounding, no context, no relationships. Flesh is hidden above all by gestures and movements, that position human beings as beings in a position in a surrounding, a being who acts in situations in relation to the world and thus appears as body-in-situation. This is described by Sartre with the term grace: "Nothing is less 'in the flesh' than a dancer even though she is nude. Desire is an attempt to strip the body of its movements as of its clothing and to make it exist as pure flesh; it is an attempt to incarnate the Other's body."[13] Gracefulness for Sartre is the "moving image of necessity and freedom", it is grounded in the active body. Practices such as bondage, which prevent the execution of movements, lead to the absence of these components and reveal the flesh of the person. The desire for making a body adopt obscene positions which expose it to all disguises and which reveal the inertia of its flesh is described by Sartre as sadistic. The sadist deprives the body of its situation, capturing and containing its freedom by looking for the fleshiness that lies hidden underneath all doing and making. The sadist wants his*her victim's body as being "entirely flesh, panting and obscene, it keeps the position that the torturers have given to it, not that which it would have taken by itself, the cords which bind it sustain it as an inert thing and, by that, it has ceased to be the object which moves spontaneously"[14].

The French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas, in turn, strikingly describes the possible shame resulting from this by means of the figure of bondage: "What appears in shame is thus precisely being tied to oneself, the radical impossibility of escaping ourselves, of hiding from ourselves: the unforgivable self-presence of the ego. We are ashamed of our nakedness when it openly reveals our being, our intimacy". And what if the confrontation with this state is now deliberately (masochistically) provoked? A fascination for such movements in BDSM practices is again expressed by the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, since for him the "paradoxical character of shame is consciously made an object in them, in order to transform it into lust. [...] For here a passive subject - the masochist - is so enthusiastic about his own, infinitely overwhelming passivity that he renounces his capacity as a subject [...]. Hence the ceremonial armor of the snares and shackles, [...] of all kinds of bondage, with the help of which the masochistic subject tries in vain to hold back and ironically fix that transferable passivity that it deliciously surpasses everywhere"[15].

If such observations are elevated to a concept such as the art of not being governed in a specific a way (but nonetheless being governed and bound), this would be accompanied by an appreciation not only of what people create and accomplish, but also of what they endure and suffer. The freedom so often longed for would then not turn out to be a kind of stock that could be disposed of. Freedom emerges momentarily in the constantly new, wayward, even energy-sapping handling of afflictions, resistance, indeterminacy and in the recognition of complex entanglements.

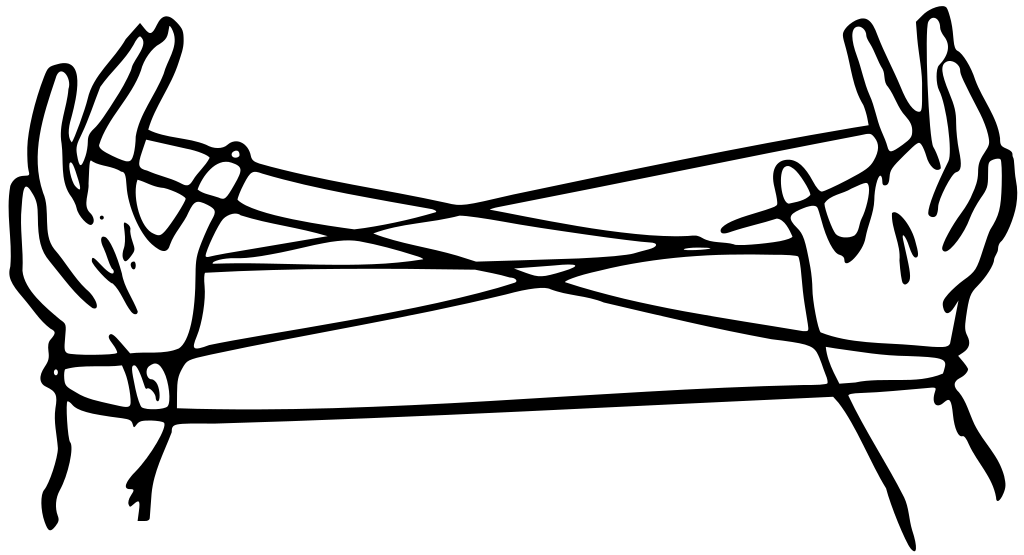

Cat's cradle: position 1, the cradle Originally from Squareman, Clarence (1916).

My Book of Indoor Games, Gutenberg.org. PD-US

For the feminist science theorist Donna Haraway such an abandonment of traditional narratives of autonomy and instead recognition of fundamental interdependencies is an unavoidable premise for living well together on this planet in the long term. To illustrate her thinking, she uses an image that is also taken from the world of strings and their potential for force-generating entanglements: String-Figures, which some readers might also know from their childhood as pattern-forming thread games. In these games, which have been and are played in a variety of cultures around the globe, the aim is to tie a closed cord around fingers and hands so that braided figures gradually form in the space in between. Their emergence can be accompanied by a narration that illustrates the pattern.

The back and forth winding of the string patterns in its playfulness points to larger things, such as "the fact that actors do not precede action, that relations take precedence". Thread games also follow an intertwining of activity and passivity, which requires a thinking of the 'in-between': "two pairs of hands are needed, and in each successive step, one is 'passive', offering the result of its previous operation, a string entanglement, for the other to operate, only to become active again at the next step, when the other presents the new entanglement. But it can also be said that each time the 'passive' pair is the one that holds, and is held by the entanglement, only to 'let it go' when the other one takes the relay."[16] Out of the entanglement of activity and passivity, Haraway develops a model in which relationships and interconnections are central: polymorphic networks that enable unexpected sides of one's own sensuous embodiment. Above all, however, the fundamental mutual interconnectedness is accompanied by a concept of responsibility that the string and bondage games illustrate:

"In passion and action, detachment and attachment, this is what I call cultivating response-ability [sic!]; that is also collective knowing and doing, an ecology of practices. Whether we asked for it or not, the pattern is in our hands."[17]

'Mme Hitchen with string bear' ~ (Anishinaabe) ~ Long Lake, Ontario 1916, F.W. Waugh, CMoH, CC-PD-old-70-expired

Which bondage patterns and stories are in our hands is in risk of being overlooked if we only exoticize the origins of rope bondage. This includes, as Haraway's cord games show, also the stories that have yet to be realized as possible future stories. Rope bondage, as romanticizing as it may sound, thus brings with it an utopian moment in which it becomes tangible that the task of grasping one's own possibilities and breaking out of a preordained destiny does not only consist in "loosening or breaking the many bonds during our lives",[18] but also to create bonds, to get tied up, to get entangled and to search together for new states of being within the existing bonds. As an adaptation of Foucault's formulation, bondage arts point out to deal with limitations, restrictions, ties and untying in an attentive and different way. The inherent vulnerability and ultimately mortality revealed by bondage not only makes the practice a breeding ground for intoxicating sensations that promise a delightful 'kick', but also has the potential to generate ethical appeals for the perception of mutual connectedness, care and responsibility for one another.

At least this is, what I have experienced and like to share.

[1] Donna J. Haraway: SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far, in: Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, Issue 3, November 2013, : https://adanewmedia.org/2013/11/issue3-haraway/ .

[2] Master "K": The Beauty of Kinbaku (or everything you ever wanted to know about Japanese erotic bondage when you suddenly realized you didn't speak Japanese), USA: King Cat Ink., 2008.

[3] Iris Därmann: Shame and Whip Violence, Pornographic Investiture Scenes in the Anti-Slavery Movement and in Marquis de Sade. In: Daniel Tyradellis (ed. for the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden): Scham. 10 Essays. Accompanying book to the exhibition: 100 reasons to be ashamed, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2017, p. 99.

[4] Edward B. Tylor: Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom, London: John Murray, 1871.

[5] See: Edwin A Dawes: The Great Illusionists, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, 1979. And: T.I.E.S. - The International Escapologist Society, http://www.tiesociety.webs.com

[6] See: Frank Cullen and Florence Hackerman: Vaudeville, Old and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, London: Routledge, 2006, p. 114.

[7] Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh: One Year Art/Life Performance: Interview with Alex and Allyson Grey (1984), in: Kristine Stiles (ed.): Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings, University of California Press, 1996, p. 907ff.

[8] Etymologically, kink derived from the 1670s, meaning "knot-like contraction or short twist in a rope, thread, hair, etc., originally a nautical term, from Dutch kink "twist in a rope" (also found in French and Swedish), which is probably related to Old Norse kikna "to bend backwards, sink at the knees" as if under a burden" (see kick (v.)). Figurative sense of "odd notion, mental twist, whim" first recorded in American English, 1803, in writings of Thomas Jefferson; specifically "a sexual perversion, fetish, paraphilia" is by 1973 (by 1965 as "sexually abnormal person").

[9] Furthermore, the mythological meaning of the many small ropes, the woven threads and cords can be pointed out, on the occasion of which the media theorist Gunnar Schmidt refers to the "coupling of woman and thread" in Arachne and many others: "Klotho, Neith, Penelope, Philomela, Holda, Zirze, Kalypso, Helena, Pandora, Paivatar, Chih-Nii, Habetrot - when it comes to spinning and weaving, mythical storytelling presents itself across cultures as a cosmos of the female". Gunnar Schmidt: Aesthetics of the thread. On the medialization of a material in avant-garde art, Bielefeld: transcript, 2007, p. 13.

The practices of rope bondage and shibari/kinbaku also have their gender-specific peculiarities, for example when the larger number of male riggers and female bunnies is strikingly remarkable - a fact that can only be hinted at in this context.

[10] See i.a. Neville Twitchell: The Politics of the Rope, Bury St. Edmunds: Arena Books, 2012.

[11] See i. a. Black Lives Matter activists go on trial over protest in Nottingham, Man and three women accused of unlawful obstruction of highway as court hears they lay across streetcar lines while tied together, in: The Guardian, UK News, 03.11.2016: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/nov/03/black-lives-matter-uk-activists-trial-protest-nottingham (last accessed on 26.06.2018); or: Protesters Tie Themselves to Trees in Bid to Save Them, in: L.A. Times, The Local Review, 23.02.1999: http://articles.latimes.com/1999/feb/23/local/me-10815 .

[12] Michel Foucault, "Qu'est-ce que la critique?," p. 37. See Judith Butler, "Critique, Dissent, Disciplinarity," Critical Inquiry, vol. 35, no. 4 (2009), 791-792 and Daniele Lorenzini and Arnold I. Davidson, "Introduction," in Foucault, Qu'est-ce que la critique? suivi de La culture de soi, p. 17.

[13] Jean-Paul Sartre: Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Washington Square Press, 1984 (orig. 1945), p. 389.

[14] Ibid, 474.

[15] Giorgio Agamben: Was von Auschwitz bleibt - Das Archiv und der Zeuge, transl. by Stefan Monhardt, Frankfurt aM: Suhrkamp, 2003, p. 93ff.

[16] Donna Haraway: Staying with the Trouble, Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures (Experimental Futures: Technologocal Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices), Durham & London, Duke University Press, 2016, p. 14.

[17] Ibid, p. 34.

[18] Nathalie Sarthou-Lajus: Lob der Schulden, transl. by Claudia Hamm, Berlin: Klaus Wagenbach 2013, p. 86.